Shaing Responsible AI Globally.

AI Law & Regulation

AI law is vital, but it is also complex and fast-changing.

Here, you’ll find a clear overview of global AI regulations — and what they mean for companies that develop AI and for people who use it.

Understand global AI laws to ensure compliance, build trust, and gain a competitive advantage.

AI law may sound complicated, but this guide makes it clear and practical. We’ll walk you through the main rules in Europe, the United States, China, and the Middle East, explaining what they mean in everyday life and in business. Along the way, you’ll see how these systems overlap, where they differ, and why that matters. Most importantly, you’ll discover how following the rules can actually open doors to trust, innovation, and new opportunities.

Table of Content:

- Why AI Law Matters Now

- Global Trends in AI Regulation

- The European Union: The AI Act as a Global Benchmark

- United States: A Patchwork Approach

- China: Strict State Control and Rapid Regulation

- Middle East: AI as a Growth and Innovation Strategy

- Comparative Analysis: East vs West vs Emerging Markets

- Practical Guidance for Businesses

- Preparing for the Future

- Resources & Updates

1. Why AI Law Matters

Artificial Intelligence has already transformed daily life, business operations, and societal infrastructure. It powers the recommendations you see on streaming platforms, automates customer support, predicts financial risk, scans medical images, and even drafts legal documents. Yet, as AI grows more sophisticated and pervasive, the legal structures designed to control, guide, and hold these systems accountable lag far behind. What exists today is a fragmented, opaque, and inconsistent regulatory landscape:

- Europe races ahead with the ambitious AI Act,

- the United States relies on a patchwork of sectoral rules and guidance,

- China enforces strict state-centric controls, and

- regions like the Middle East experiment with innovation-driven frameworks.

No single authority, jurisdiction, or coalition has global oversight of AI, leaving both companies and individuals exposed to legal uncertainty, operational risk, and unforeseen harm.

This fragmented environment creates immediate and tangible problems. Consider a company developing a medical AI system in the U.S., trained on European patient data, and deployed via cloud infrastructure hosted in Asia. Which legal standards apply? Whose privacy, safety, or liability rules take precedence? The current reality is a jigsaw of inconsistent and sometimes contradictory laws, forcing companies to navigate a complex maze. The result: high compliance costs, slowed innovation, and, in some cases, inadvertent legal violations. For individuals, this fragmentation means uncertainty and risk. Citizens cannot easily know if AI systems impacting their lives — in healthcare, banking, or law enforcement — are safe, fair, or accountable.

Already, real-world cases underscore the stakes. Artists and publishers have sued AI companies for training generative models on copyrighted material without consent, raising questions about intellectual property at scale. Yet copyright is only the visible tip of a much larger problem. What happens when AI misdiagnoses a patient, drives an autonomous vehicle into harm, or decides credit eligibility in ways that reinforce bias and inequality? Who is responsible — the developer, deployer, cloud provider, or end user? Courts worldwide are only beginning to answer these questions.

Consider a few striking examples: In the United States, a man was wrongfully arrested after a facial recognition system misidentified him, showing the tangible risks when institutions over-rely on AI. Hospitals testing diagnostic algorithms have found bias baked into training data, leading to unequal treatment outcomes. Deepfake technology has already been exploited to spread fraud and political misinformation across borders. These incidents reveal that AI law is not just about copyright or compliance. It is about safety, accountability, fairness, and the fundamental trust society places in digital systems.

For companies, the risks are enormous. A biased credit scoring AI could trigger lawsuits, regulatory fines, or reputational damage, even if developers did not intend harm. Marketing algorithms that scrape consumer data globally could inadvertently violate privacy laws in some regions while complying with others.

Without a unified regulatory framework, businesses face constant uncertainty, creating both ethical and strategic challenges. We live in a time of Regulatory arbitrage. Developing AI in regions with weaker safeguards and exporting it to stricter markets becomes a tempting but dangerous path. For users, this means potential exposure to untested, unsafe, or unfair AI systems.

The dark side of fragmentation becomes clearer when we look ahead. If global AI regulation remains disjointed over the next 5–10 years, several scenarios could emerge:

- Autonomous systems without accountability: Self-driving cars, drones, or industrial robots may operate across borders with no clear legal responsibility, leaving victims of accidents without recourse.

- Healthcare and life-critical AI errors: AI tools in diagnostics or treatment could misclassify conditions due to biased or incomplete data, resulting in preventable harm without clear liability.

- Algorithmic discrimination at scale: Without consistent rules, AI systems used in hiring, lending, or insurance could embed and amplify social inequalities, impacting millions.

- Global misinformation and fraud: Deepfakes, AI-generated financial scams, and automated propaganda could proliferate, exploiting gaps between national enforcement regimes.

- Erosion of trust in AI: Repeated failures and unaccountable harm could slow adoption, undermine innovation, and create public backlash against AI technologies.

These scenarios are not abstract hypotheticals; early examples already exist, and the pace of AI innovation is accelerating. The longer legal frameworks remain inconsistent, opaque, or reactive, the greater the risk that harm outpaces accountability.

You see: AI law matters urgently because it defines responsibility in an era where machines increasingly make consequential decisions. For companies, it is about compliance, trust, and international competitiveness. For individuals, it is about safety, fairness, and certainty in a world increasingly mediated by AI. The stakes are immense: unregulated or poorly regulated AI is not just a corporate or technical problem; it is a societal challenge, one that will shape the ethics, security, and stability of global systems in the coming decade.

The key takeaway is that AI law is both critical and unavoidable. Ignoring it exposes companies to legal, ethical, and reputational risks. For society, it creates a web of hidden dangers that may take years to unravel. This guide seeks to illuminate the landscape, explain the risks and responsibilities, and help both businesses and users navigate a complex, high-stakes environment. Understanding AI law today is not optional — it is a prerequisite for safe, responsible, and trustworthy innovation tomorrow.

2. Global Trends in AI Regulation

Artificial Intelligence is no longer a technology confined to laboratories or tech giants’ R&D departments. It is a strategic asset, shaping economies, military capabilities, and global competitiveness, while simultaneously presenting profound societal risks. Governments, intergovernmental organizations, and standards bodies are scrambling to establish frameworks that both encourage innovation and safeguard human rights, privacy, and security. Unlike traditional technologies, AI transcends borders instantly: a model trained in one country can be deployed worldwide, influencing millions within seconds. This global nature creates a paradox — while AI offers unprecedented opportunities, it exposes gaps in regulatory oversight, leaving companies and users navigating a fragmented and opaque legal environment.

Across the world, regulators take different approaches, reflecting diverse priorities and philosophies. Some favor binding rules that carry legal obligations and penalties, while others advocate soft law approaches, emphasizing ethical principles, voluntary guidelines, or aspirational standards. The coexistence of hard and soft law highlights both the potential and the limitations of international AI governance. Soft law frameworks are flexible, adaptable, and easier to implement globally, yet they often lack enforcement power and leave companies and users exposed to legal ambiguity. Hard law, by contrast, provides certainty, enforceable obligations, and accountability, but its rigidity may stifle innovation or create barriers to global deployment.

2.1 The International Landscape: AI as Strategic Asset and Risk

AI is increasingly seen as a critical element of national and economic strategy. Nations are investing heavily in AI research, talent development, and industrial adoption. Governments recognize that AI can enhance productivity, drive competitiveness, and even define geopolitical influence. The European Union, for example, positions itself as a global leader in trustworthy AI, prioritizing human rights and safety alongside innovation. China views AI as a strategic pillar for its economic and technological future, linking governance with state oversight and national priorities. The United States emphasizes innovation and market-driven development, regulating mostly through sector-specific legislation and judicial decisions rather than sweeping national AI laws.

This uneven approach produces both opportunities and risks. For companies, the fragmented landscape creates uncertainty: compliance with one standard does not guarantee global acceptability. For individuals, it leaves them vulnerable to unaccountable AI systems, whether through bias, misinformation, or errors in high-stakes domains like healthcare, law enforcement, and finance. Without a globally coordinated regulatory framework, no region can fully ensure safety or accountability for AI applications deployed worldwide. This has already led to regulatory arbitrage, where companies exploit differences between jurisdictions to launch AI products in less regulated regions while postponing compliance elsewhere.

2.2 Soft Law vs Hard Law

Understanding AI regulation requires a clear distinction between soft law and hard law.

Soft law encompasses voluntary codes of conduct, ethical principles, and non-binding international agreements. Examples include the OECD AI Principles and UNESCO AI Ethics Recommendations. Soft law is valuable because it can be implemented quickly, adapted to local contexts, and applied across borders without waiting for formal legislation. It encourages companies to internalize ethical values and provides a foundation for responsible innovation. However, its voluntary nature means there is no guarantee of compliance, and companies may interpret principles differently or prioritize profits over ethics.

Hard law, on the other hand, includes legally binding regulations, national statutes, and enforceable international agreements. These rules carry penalties, obligations, and oversight mechanisms. The EU AI Act is the most prominent example of hard law today, establishing enforceable requirements for high-risk AI systems. Hard law provides clarity and accountability, ensuring that companies cannot simply ignore obligations. Yet hard law can be slow to develop, inflexible, and fragmented, leaving global gaps. Companies operating internationally must navigate a patchwork of overlapping hard and soft law regimes, which can create confusion, legal risk, and compliance costs.

2.3 Key Global Initiatives

Several initiatives attempt to provide a global baseline for AI governance. While none are enforceable worldwide, they are influential in shaping corporate behavior, national strategies, and international negotiations.

(1) OECD AI Principles

Adopted in 2019 by 42 countries, including major AI players, the OECD AI Principles are among the first internationally recognized guidelines for trustworthy AI. They emphasize human-centered values, including fairness, transparency, accountability, robustness, and respect for human rights.

For companies, adherence to OECD Principles signals a commitment to responsible AI, potentially influencing investors, clients, and regulators. For users, these principles aim to protect rights and foster trust. However, because the OECD principles are voluntary, there is no formal enforcement mechanism, and companies may choose to implement them selectively. Nonetheless, they serve as a common reference point in international debates and national strategies.

Reality Check for the OECD AI Principles:

- Microsoft publicly aligned its development of AI tools like Azure OpenAI Service with OECD principles, emphasizing fairness, transparency, and human oversight. In practice, this means implementing human-in-the-loop mechanisms for decision-making and auditing AI outputs to prevent bias.

- Yet challenges remain. Stability AI, which developed generative models trained on scraped copyrighted content, cites OECD principles in its corporate ethics statements, but courts in the U.S. are still hearing lawsuits over copyright infringement. This highlights a key gap: soft law guidance does not prevent legal liability. For companies, OECD alignment builds reputational credibility, but it cannot replace national laws. For users, this means that even AI systems claiming to follow ethical guidelines may still expose them to legal or financial risk.

(2) UNESCO AI Ethics Recommendation

In 2021, UNESCO adopted a global recommendation on AI ethics, emphasizing human rights, inclusion, diversity, and environmental sustainability. Unlike OECD principles, UNESCO’s framework explicitly addresses societal and cultural values, encouraging countries to embed ethics into law, governance structures, and corporate practices.

The recommendation highlights that AI is not only a technological challenge but also a moral and societal one. Companies that engage with UNESCO’s guidance can gain reputational benefits and preempt regulatory pressure, while governments may use it as a reference for crafting national policies. However, like all soft law, enforcement relies on political will and voluntary adoption, leaving gaps in accountability.

Reality Check for the UNESCO AI Ethics Recommendation:

- UNESCO’s recommendation emphasizes human rights, inclusion, and cultural sensitivity. A striking case comes from AI in educational assessment. In Brazil, pilot AI tools were tested to grade student essays. While the algorithms improved grading efficiency, they disproportionately disadvantaged students from rural regions, reflecting linguistic and cultural biases in training data. Adhering to UNESCO’s principles would require adjustments to ensure equity and inclusivity.

- Another example comes from AI recruitment systems in multinational firms. Algorithms that appear neutral on the surface may embed biases against women or minority candidates, reflecting broader societal inequities. UNESCO’s framework encourages companies to consider these hidden harms and embed diversity checks into AI governance. The lesson is clear: ethics without enforcement still requires proactive attention, or harm can occur unnoticed.

(3) ISO/IEC Standards

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) have developed a series of standards for AI governance and risk management. These standards provide technical guidance for robustness, safety, interoperability, and auditability of AI systems.

For businesses, ISO/IEC standards offer practical tools to structure internal AI governance, demonstrate due diligence, and prepare for future regulatory requirements. For users, these standards help ensure safer, more reliable systems. While compliance is voluntary, adoption can become a de facto requirement as regulators and clients increasingly expect alignment with ISO/IEC guidance.

Reality Check for the ISO/IEC Standards:

- The ISO/IEC standards focus on AI governance, risk management, and safety. Companies like Siemens have adopted ISO-aligned frameworks for industrial AI, including predictive maintenance systems for critical infrastructure. By systematically auditing data sources, performance metrics, and safety redundancies, Siemens demonstrates compliance and reduces operational risk.

- However, adoption is uneven. Smaller start-ups may bypass these standards to accelerate deployment. One example is an AI-powered drone delivery startup in Southeast Asia, which faced operational setbacks when its autonomous navigation system collided with infrastructure due to lack of formal safety audits. ISO/IEC standards, if universally adopted, could have mitigated such incidents. The takeaway: technical standards can prevent catastrophic failures, but voluntary adoption leaves critical gaps.

(4) G7 Hiroshima AI Process

In 2023, the G7 nations established the Hiroshima AI Process, fostering high-level cooperation on AI governance, ethics, and responsible deployment. The initiative reflects a shared recognition among leading economies that AI regulation is both strategic and urgent.

While political in nature, the G7 process sets signals for companies about emerging global norms. Firms that align with G7 priorities can position themselves as leaders in trustworthy AI, gain strategic advantage, and anticipate cross-border regulatory trends. However, the process highlights a recurring theme: coordination exists at a high political level, but enforcement and adoption remain uneven, leaving gaps in the regulatory web.

Reality Check for the G7 Hiroshima AI Process:

- The G7 Hiroshima AI Process illustrates international political alignment. Companies that operate globally, like Toyota and DeepMind, monitor G7 guidelines to anticipate regulations affecting AI deployment, particularly in autonomous vehicles and robotics. The process signals emerging expectations around accountability, human oversight, and cross-border data governance.

- Yet political alignment does not automatically translate into enforceable rules. In practice, a self-driving vehicle developed in Japan according to G7-aligned guidelines could encounter stricter liability laws if deployed in Germany, illustrating the gap between policy coordination and binding legal frameworks. Users may assume AI systems are “safe” because they follow global recommendations, but this is not necessarily guaranteed.

2.4 Implications and Limitations

Together, tese initiatives illustrate a key tension in global AI regulation. On one hand, principles, standards, and political processes offer guidance, ethical orientation, and a shared language. On the other hand, enforcement is inconsistent, adoption is voluntary in many regions, and no global authority exists to oversee AI deployment comprehensively. This fragmented landscape leaves companies exposed to legal uncertainty, users vulnerable to hidden risks, and regulators struggling to keep pace with technology.

Consider generative AI models trained on copyrighted works, deployed internationally. They may comply with local principles in one jurisdiction while violating copyright law in another. Autonomous vehicles or AI medical devices may meet technical standards in one country but fail regulatory requirements elsewhere, with serious consequences for safety and liability. Even organizations committed to ethical AI face dilemmas when principles conflict with market pressures or competitive incentives.

The gaps in enforcement also encourage regulatory arbitrage. Companies may develop AI in loosely regulated regions and later export to stricter markets, leaving the global system patchy and uneven. For individuals, this can translate into exposure to unsafe systems, discriminatory algorithms, or misinformed decisions driven by AI.

2.5 Looking Ahead

The global trends in AI law suggest that fragmentation will persist in the short term, even as initiatives like the OECD, UNESCO, ISO/IEC standards, and G7 processes provide guidance. Companies must navigate a complex web of voluntary and mandatory frameworks, balancing innovation with accountability. Users and societies must recognize that AI’s risks extend beyond obvious harms — from bias and misinformation to opaque decision-making and cross-border legal ambiguity.

Ultimately, understanding these global trends is essential for anyone engaged with AI — whether designing systems, deploying products, or using AI-powered services. Awareness of principles, standards, and political processes allows companies to anticipate change, prepare governance structures, and convert compliance into a strategic advantage. For individuals, it equips them to advocate for safer, fairer, and more transparent AI, highlighting that the conversation about AI law is not abstract — it is fundamental to shaping the technology that increasingly governs everyday life.

3. The European Union: The AI Act as a Global Benchmark

When the European Union first unveiled the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) in 2021, it captured global attention. Just as the GDPR had previously reshaped how companies manage personal data, the EU now aims to do the same for AI. The ambition is bold: to make Europe the undisputed leader in “trustworthy AI”, setting a global standard for both innovation and accountability.

The motivations behind this initiative are both pragmatic and principled. On the one hand, European policymakers are determined to prevent the kinds of harms that arose from unregulated digital technologies, from social media manipulation to mass data breaches. They recognize that AI’s rapid development carries the potential for bias, opaque decision-making, and even societal disruption if left unchecked. On the other hand, the EU sees regulation as an opportunity to harmonize legal frameworks across its 27 member states. By creating a single, coherent structure, the EU aims to reduce fragmentation, simplify compliance for companies, and establish a clear baseline for ethical and safe AI deployment.

For companies, the AI Act is not merely a legal obligation; it is a call to redesign internal processes, governance structures, and risk management strategies. For individuals, it promises more transparency, accountability, and protection from potentially harmful AI systems. And for the global community, the EU’s approach is likely to serve as a benchmark — much as GDPR has done in the realm of privacy — influencing corporate behavior and legislative initiatives worldwide.

Consider, for instance, the European debate over social scoring systems. While still largely hypothetical in many parts of the world, EU policymakers preemptively prohibited such applications, reflecting the region’s commitment to safeguarding democratic values and human dignity. Similarly, the Act addresses manipulative AI systems and real-time biometric surveillance, signaling that technology must serve society, not exploit it. These examples underscore the EU’s dual focus: protecting citizens while fostering innovation within defined, ethical boundaries.

3.1 Scope and Definitions

The AI Act casts a wide net, applying to multiple actors across the AI ecosystem. It covers providers who develop AI systems, deployers who integrate or operate AI, and importers and distributors who bring AI products to the EU market. The definition of an “AI system” is intentionally broad, encompassing not only machine learning models but also logic- and knowledge-based approaches, as well as statistical methods. The aim is to future-proof the legislation, ensuring that innovations yet to emerge cannot evade oversight simply by exploiting definitional loopholes.

This breadth carries implications for global companies. Even businesses that do not identify themselves as AI developers may find their products subject to regulation if they incorporate algorithms capable of making automated decisions or influencing human behavior. A multinational deploying a marketing personalization engine or a predictive maintenance tool might suddenly fall within the Act’s scope, requiring compliance with rigorous documentation, risk management, and transparency standards.

Importantly, the AI Act has extraterritorial reach, echoing the global influence of GDPR. Any company worldwide offering AI products to EU citizens, or whose systems generate outputs affecting individuals in the EU, must comply. For a U.S.-based AI startup, this means that geographic location no longer shields them from European oversight. Ignoring the AI Act is simply not an option if they wish to operate in the EU market.

3.2 The Risk-Based Framework

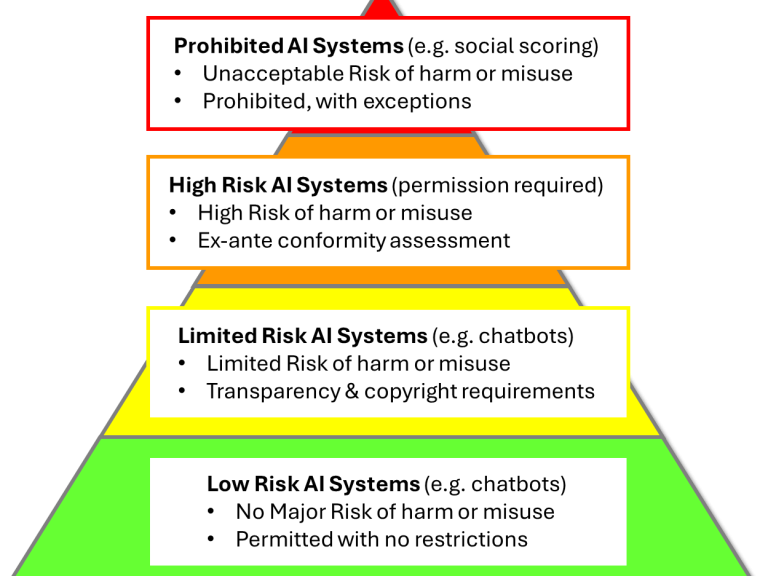

At the heart of the AI Act lies its risk-based approach, a tiered system designed to balance innovation and protection. Unlike a one-size-fits-all regulation, it categorizes AI systems according to the potential harm they may pose to individuals or society.

(1) Prohibited practices represent the highest concern. AI applications deemed incompatible with European values — including social scoring, manipulative systems exploiting vulnerable groups, and indiscriminate biometric surveillance — are explicitly banned, with only narrowly defined exceptions for law enforcement or public safety. By setting these boundaries, the EU makes clear that technological capability does not equate to ethical acceptability.

(2) High-risk AI systems form the largest regulatory category. These are applications that can directly impact human rights or safety, spanning healthcare diagnostics, employment screening, critical infrastructure, credit scoring, migration controls, and law enforcement tools. Providers and deployers of high-risk AI must adhere to strict obligations, including robust risk management, rigorous data governance, transparency, and human oversight. For instance, a recruitment AI that screens applicants based on prior hiring decisions must demonstrate that its training data is unbiased and representative. Failure to comply could lead to legal action or regulatory scrutiny.

(3) Limited-risk AI includes systems with less direct societal impact, such as chatbots or content-generating algorithms. Obligations here focus mainly on transparency: users must know when they are interacting with AI and when outputs might influence decisions affecting them.

(4) Minimal-risk AI, finally, encompasses the vast majority of applications, from spam filters to video games. These systems face no mandatory legal requirements but are encouraged to adopt voluntary codes of conduct to foster responsible innovation. This tiered structure allows the EU to concentrate regulatory energy where it matters most, avoiding unnecessary burdens on benign applications while safeguarding citizens from high-stakes risks.

The EU AI Act - Risk Classification

High Risk

Highly regulated AI applications with the potential to cause significant harm in case of failure or system misuse (e.g. recruting, law enforcement).

Minimal Risk

All AI applications with minimal risk for harm or misuse (e.g. AI-empowrred spam filters). Can be depolyed without further restrictions.

Unacceptable Risk

The highest AI risk level. AI appplications are prohibited if the incorporate a risk of e.g. manipulation or social disruption.

Limited Risk

AI applications with limited risk of harm like of chatbots or emotion recognition systems. Users must be enformed that they ineract with AI.

3.3 Obligations for Companies

For companies handling high-risk AI, the Act imposes comprehensive requirements. Organizations must implement risk management systems that identify, evaluate, and mitigate potential hazards throughout the AI lifecycle. Data governance is critical: training and validation datasets must be relevant, representative, and as free from bias as possible. Comprehensive documentation and record-keeping enable regulatory authorities to audit AI systems effectively. Transparency obligations ensure that users understand when AI is influencing outcomes that affect them. Human oversight mandates that AI cannot operate fully autonomously in critical areas; humans must retain the ability to intervene. Post-market monitoring obligates companies to track system performance, reporting incidents or malfunctions to authorities.

Deployers, who integrate AI into operations, share responsibility. They must ensure proper use, monitor outputs, and train personnel on AI limitations. Even small firms will need internal governance structures, clearly defined responsibilities, and compliance frameworks, although EU guidance promises to help SMEs navigate these requirements.

Consider a real-world illustration: a European health-tech company using AI for medical image analysis discovered during post-market monitoring that the system performed less accurately on images from older demographic groups. Compliance with the AI Act required immediate corrective action, reporting to authorities, and adjustment of training datasets. This example shows that compliance is dynamic, not a one-time checklist.

3.4 Enforcement and Penalties

Enforcement mirrors the GDPR model, with national supervisory authorities in each member state coordinated by a European AI Board. Non-compliance carries substantial fines: up to €35 million or 7% of global turnover for prohibited AI practices, up to €15 million or 3% for breaches related to high-risk systems, and smaller fines for less severe violations.

These penalties are intentionally high, signaling that AI regulation is a boardroom concern, not a technical footnote. Companies can no longer treat AI as an experimental side project; governance, legal oversight, and technical risk management must all operate in tandem.

Interplay with Other Laws

The AI Act interacts with existing EU regulations, creating a complex web of obligations. GDPR governs personal data processing, ensuring lawful handling, consent, and data subject rights. Product safety legislation applies to AI-enabled machinery, medical devices, and other regulated products. Sector-specific rules, such as those in finance or healthcare, overlay additional compliance requirements. For companies, this creates both complexity and reinforced accountability. AI compliance cannot be siloed; it must integrate seamlessly with broader corporate governance.

Implications for Businesses

For companies, the AI Act presents a dual reality: challenge and opportunity. Compliance requires significant investment in legal, technical, and operational processes, which can be daunting for SMEs. Early preparation, however, offers strategic benefits. Firms demonstrating trustworthy AI can gain customer confidence, attract investment, and differentiate themselves in competitive procurement processes. Compliance may even become a marketable asset: companies could advertise “AI Act-compliant solutions” as a hallmark of reliability and ethical responsibility.

Implications for Individuals and Society

For citizens, the AI Act promises greater safety, transparency, and fairness. High-risk AI systems, from recruitment algorithms to diagnostic tools, will be subject to stricter standards, reducing risks of discrimination, errors, or hidden bias. The regulation also aims to build public trust, encouraging broader adoption of AI where benefits can be realized, such as in healthcare, education, and public services. Individuals gain not just protection, but visibility into AI’s role in daily life, fostering informed engagement with technology.

Practical Next Steps for Companies

Immediate actions for businesses include

- mapping AI systems,

- classifying risk levels,

- developing compliance roadmaps,

- appointing an AI officer, and

- aligning with international standards like ISO/IEC governance frameworks or the NIST AI Risk Management Framework.

Waiting until enforcement begins will likely leave companies scrambling, facing high costs, and potential reputational damage. Early adoption of best practices can transform regulatory compliance into a competitive advantage.

The AI Act has comes into force in stages between 2025 and 2027. High-risk systems face obligations first, while prohibited practices are banned outright. By 2027, most provisions will apply globally to companies offering AI services to the EU market. The act’s influence is expected to ripple far beyond Europe. Non-EU companies may adopt its standards voluntarily to simplify compliance, signal trustworthiness, and reduce legal risk. Just as GDPR reshaped global data protection norms, the AI Act is poised to redefine global expectations for ethical, transparent, and accountable AI.

For businesses, the takeaway is clear: AI regulation is no longer theoretical. Companies must prepare, adapt, and integrate compliance into core strategies. Those who act early will not just survive but thrive, while those who delay may face financial penalties, operational setbacks, and reputational harm.

4. United States: A Patchwork Approach

When it comes to artificial intelligence, the United States occupies a paradoxical position. It is simultaneously the world’s most important hub for AI innovation and yet one of the least cohesive in its approach to regulating the technology. Silicon Valley, Seattle, Boston, and Austin have become the epicenters of AI research and commercialization, but Washington, D.C., has not yet crafted a comprehensive framework that matches the scale and speed of this transformation. Instead, U.S. regulation of AI is unfolding through a patchwork of initiatives: federal “soft law” guidance documents, state-level legislation, and the assertive use of existing consumer protection and anti-discrimination powers by agencies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC).

This fragmented model is both a strength and a weakness. It allows flexibility, experimentation, and a bottom-up evolution of norms. But it also creates opacity, uncertainty, and legal asymmetry: the rules that apply in California may not apply in Texas; what the FTC sees as deceptive AI use may or may not overlap with what the Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutes as fraud. For companies, especially those operating across borders, this means that the U.S. is both a trendsetter and a regulatory minefield.

4.1 Soft Law as Compass: The White House AI Bill of Rights

The most visible attempt to establish a moral and political baseline for AI use in the United States came in 2022, when the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) released the “Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights". Importantly, this is not a binding legal document. It is, as American policymakers often describe it, a form of “soft law” — a guiding set of principles that agencies, companies, and researchers are encouraged, but not compelled, to follow.

The AI Bill of Rights is structured around five broad protections:

- The right to safe and effective systems: AI should not expose users to unsafe, untested, or reckless deployment.

- The right to protection against algorithmic discrimination: AI should not perpetuate or amplify bias.

- The right to data privacy: citizens should have agency over how their data is used in AI.

- The right to notice and explanation: people should know when AI is being used and how decisions are made.

- The right to human alternatives, consideration, and fallback: when AI impacts rights or well-being, humans must remain accessible as decision-makers.

On the surface, these rights echo constitutional ideals of liberty and fairness, adapted to a technological age. But beneath the rhetoric lies a stark reality: there is no enforcement mechanism. If a company deploys a biased hiring algorithm, it cannot be sued directly under the “AI Bill of Rights.” If a hospital rolls out a faulty diagnostic AI that puts patients at risk, victims cannot claim damages by invoking this document.

Critics therefore dismiss the initiative as little more than a symbolic gesture. Yet symbols matter. The AI Bill of Rights has already influenced the way agencies talk about AI and how journalists frame public debate. More importantly, it serves as a benchmark against which civil society groups and advocacy organizations measure corporate behavior. A tech giant that claims to act responsibly but ignores these five principles risks reputational harm, even if it avoids direct legal penalties.

4.2 NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework: Technical Guidance with Legal Echoes

Where the White House offers broad principles, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides detail. NIST is not a regulator in the classic sense; it is a standards body with deep ties to industry. But in January 2023, NIST published its AI Risk Management Framework (AI RMF 1.0), a document that is quickly becoming one of the most influential non-binding frameworks in global AI governance.

The NIST framework is designed to help organizations identify, measure, and mitigate risks associated with AI. It organizes risks into categories such as safety, reliability, security, privacy, fairness, and accountability. Unlike the EU’s prescriptive rules, the AI RMF is flexible: it encourages organizations to tailor risk management practices to their specific context.

What makes the NIST framework remarkable is its indirect legal power. U.S. regulators and courts often look to NIST standards as a “reasonable practices” benchmark. For example, in cybersecurity, failure to adopt NIST recommendations has been used as evidence of negligence. It is not difficult to imagine a future lawsuit in which a plaintiff’s lawyer asks: “Did your company align its AI processes with the NIST AI RMF?” If the answer is no, that absence may be portrayed as a failure of due diligence.

Consider a scenario: A fintech company uses AI to decide loan applications. A group of rejected applicants sues, alleging algorithmic bias. While the company might argue that it complied with existing anti-discrimination laws, a court could still scrutinize whether the company had followed widely recognized guidance such as the AI RMF. In this way, what begins as “voluntary” becomes a shadow form of obligation.

The AI RMF also resonates internationally. Many multinational firms headquartered in the U.S. are adopting it as their internal governance standard, because it aligns with risk-based approaches in Europe and Asia without imposing strict legal commands. The U.S., through NIST, is thus exporting governance by influence rather than governance by statute.

4.4 Filling the Federal Void: States and Agencies Step In

The United States does not yet have a comprehensive federal AI law. But this does not mean AI operates in a regulatory vacuum. Instead, two forces are filling the gap: state legislatures and national regulatory agencies. Together, they create a patchwork of rules and enforcement mechanisms that companies must navigate.

On the state level, California has been the most ambitious. Its California Consumer Privacy Act, later expanded into the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), gives residents significant rights over how their data is used in automated decision-making. Illinois has gone even further with its Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), which tightly regulates the use of facial recognition and other biometric data. This law is not symbolic — it has triggered massive lawsuits, including billion-dollar settlements with Meta over unlawful biometric data collection. Meanwhile, New York has introduced rules that require employers to disclose and audit their use of AI in hiring, setting a precedent for workplace transparency.

The result is a legal environment where individuals enjoy vastly different protections depending on where they live. In Illinois, a resident can challenge a company’s misuse of biometric data in court. In states without such laws, that same misuse might remain unaddressed. For businesses, this patchwork translates into high compliance costs and operational headaches. Many companies choose to adopt the strictest state rules nationwide, just to avoid the chaos of juggling conflicting obligations.

Federal agencies are also stepping in. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has warned companies against making exaggerated claims about “AI-powered” products, calling such marketing potentially deceptive. It has also targeted cases where algorithms unfairly discriminated against consumers. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) has begun investigating whether hiring algorithms disadvantage candidates based on race, gender, or disability. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) has raised alarms about opaque “black box” systems in credit scoring and lending, making clear that financial AI must comply with long-standing fair lending laws.

What is striking is that these agencies do not need new AI-specific statutes to act. Instead, they apply existing consumer protection, anti-discrimination, and financial rules to new technological contexts. For companies, this creates uncertainty: even if they believe they are operating in an “unregulated” space, agencies can still hold them accountable. For individuals, it means there is at least some recourse if AI harms them — though much depends on whether regulators recognize a violation and choose to pursue it.

Taken together, state laws and federal agency enforcement form a kind of patchwork substitute for comprehensive federal legislation. It is imperfect, uneven, and often reactive rather than proactive. Yet it is also dynamic and influential: through lawsuits, settlements, and agency rulings, these measures are quietly shaping how AI is built, marketed, and deployed across the country.

4.4 The Problem of Fragmentation

Taken together, the AI Bill of Rights, the NIST framework, the activities of some US states and federal agencies reveal the paradox of American AI law. On one hand, they establish a moral and technical foundation for safe, fair, and trustworthy AI. On the other hand, they remain advisory, not mandatory. Unlike the European Union’s AI Act, which comes with penalties and compliance deadlines, the U.S. approach is voluntary.

The result is fragmentation. Different companies adopt different standards. Some states legislate aggressively, others not at all. Agencies interpret their mandates creatively but inconsistently. For innovators, this creates a gray zone: the rules are vague enough to allow experimentation, but opaque enough that missteps can trigger lawsuits or regulatory crackdowns.

This opacity also undermines global clarity. Imagine a startup building a medical AI tool in California. It might comply with state privacy laws, align with NIST risk management, and reference the AI Bill of Rights. But if that same company tries to launch in Europe, it may face entirely different requirements under the AI Act. Meanwhile, if it expands to Asia, yet another set of frameworks applies. No single U.S. principle provides assurance of global compliance.

Please be aware: The lack of a comprehensive federal law does not mean the U.S. is irrelevant in shaping AI governance. Quite the opposite: because of its economic and technological power, American “soft law” often sets de facto standards worldwide. A voluntary NIST framework can matter just as much as a binding European regulation when multinational corporations adopt it globally. But the flip side is risk. If the patchwork becomes too incoherent, companies may exploit loopholes, consumers may suffer harms without recourse, and the U.S. may lose credibility as a steward of safe AI.

5. China - Strict State Control and Rapid Regulation

China has emerged as one of the fastest-moving regulators in the global AI landscape. Unlike the European Union, which favors risk-based frameworks, or the United States, which relies on a patchwork of federal guidance and state laws, China has chosen a direct, state-driven approach that combines tight control with rapid innovation. Its regulatory philosophy is shaped by two priorities: harnessing AI as a strategic economic and technological asset, and ensuring that digital platforms operate within strict boundaries that preserve social stability, national security, and ideological alignment.

The resulting framework is neither piecemeal nor optional. It integrates AI-specific laws with broader data, cybersecurity, and personal information rules, creating a tightly interwoven system that affects both domestic and foreign companies. In this chapter, we examine the two cornerstones of China’s early AI regulation: the Algorithm Regulation Law (2022), which disciplines recommendation systems, and the Generative AI Regulation (2023–2024), which governs content creation tools. Together, they illustrate China’s unique balance of control and innovation, offering lessons for businesses and regulators worldwide.

5.1 The Algorithm Regulation Law (2022): Building the Foundations of Control

In March 2022, China took a historic step in AI governance by introducing the Provisions on the Administration of Algorithmic Recommendation for Internet Information Services, widely referred to as the Algorithm Regulation Law. This law marks China as the first major country to enact legally binding rules specifically targeting algorithmic systems. While the European Union focuses on risk-based categories and the U.S. relies on fragmented enforcement, China chose a direct, state-driven approach that ties AI regulation into the broader machinery of governance, national security, and social management.

The motivations behind the law are clear. In China, recommendation algorithms power the majority of online experiences: from social media feeds and e-commerce product rankings to video streaming and ride-hailing dispatch systems. These systems shape what billions of users see, buy, and consume, giving them immense societal influence. Chinese regulators observed that unmonitored algorithms could manipulate user behavior, reinforce addiction, or even amplify content with destabilizing political or social effects. The law, therefore, is not merely about protecting consumers—it is about preserving social stability and asserting state control over digital flows.

At the heart of the law is the registration and oversight requirement. Companies operating platforms with recommendation capabilities must register their algorithms with the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). The registration process requires disclosure of algorithmic logic, the types of data used for training and personalization, and the intended use of the system. Platforms must also demonstrate that users have meaningful control over algorithmic outputs, including the ability to opt out of personalization entirely. This is not a trivial feature: companies must prove that turning off recommendations actually works in practice, which affects interface design, backend systems, and user experience strategies.

Beyond registration, the law enforces several user-centric obligations. Algorithms cannot exploit vulnerabilities or induce addictive behavior, particularly for minors. They must also avoid discriminatory or unfair treatment, such as unjustified price variations or preferential ranking that harms sellers or consumers. Providers are expected to maintain transparent processes and logs, enabling regulators to audit their systems and understand why certain content, offers, or results were presented to users.

Content governance is another key pillar. Any content surfaced or amplified by algorithms must comply with national standards. Outputs that could undermine “national unity, social stability, or public morality” are explicitly prohibited. While these terms are broad, they give regulators wide discretion to intervene when algorithmic outcomes conflict with state priorities. This blend of digital governance and ideological oversight sets China apart from Western approaches, where algorithmic fairness or privacy is usually the primary concern.

The law also imposes duties for vulnerable populations, particularly minors. Platforms must implement safeguards such as time limits, reduced exposure to addictive content, and parental controls. These measures are mandatory, not optional. They directly affect design choices, revenue models, and engagement strategies for platforms that have historically relied on unlimited user attention. Companies need to balance profitability with compliance, often restructuring core engagement mechanics to satisfy regulators.

Enforcement under the law is administrative and swift, leveraging China’s existing regulatory infrastructure. The CAC can issue fines, suspend algorithmic services, or even mandate corporate restructuring for serious violations. Early enforcement examples show that platforms must act quickly: social media apps were required to adjust feed algorithms, video platforms revised content ranking systems, and e-commerce operators re-evaluated promotional and product display logic. The law is not purely reactive; it encourages preemptive internal governance, such as algorithm audits, human oversight mechanisms, and compliance teams capable of responding to regulatory inquiries.

For businesses, the implications are significant. Any platform with algorithmic recommendations must integrate compliance into the core of its AI strategy. Legal, technical, and product teams cannot operate in silos; they must coordinate to ensure registration, fairness, content moderation, and transparency. Moreover, foreign companies entering the Chinese market face additional hurdles, including the requirement for local representation, alignment with state-approved content standards, and data localization obligations that tie closely into Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and Data Security Law (DSL) frameworks. Ignoring these requirements is not optional: non-compliance can result in operational shutdowns or legal sanctions.

For users, the law promises enhanced agency, transparency, and protection, particularly for minors. People can see why certain content is recommended, have the option to switch off personalization, and enjoy clearer channels to report algorithmic abuse or unfair treatment. Yet these protections exist within a system designed to ensure state oversight, meaning the benefits are tightly controlled by the government.

Strategically, the Algorithm Regulation Law also serves as a foundation for China’s broader AI governance framework. It sets precedents for how the state can intervene in AI-driven platforms, demonstrates the feasibility of algorithm registration and auditing at scale, and signals to domestic and foreign companies alike that AI is not merely a technical challenge—it is a matter of legal, social, and political responsibility. By codifying these expectations, China creates a model that other countries with strong state control may emulate, even as democratic nations debate transparency and accountability.

In short, the 2022 Algorithm Regulation Law transformed China’s AI landscape. It demonstrates that regulation can be immediate, detailed, and integrated into broader governance priorities. Companies must rethink AI strategy not just in terms of efficiency or user engagement, but through the lens of legal compliance, social responsibility, and political alignment. For the global community, it provides a vivid example of how a major economy can combine control, oversight, and rapid innovation under a single regulatory philosophy, setting the stage for the next wave of AI governance—generative AI.

5.2 The Generative AI Regulation (2023–2024): Managing the AI Revolution

Following the foundational steps of the Algorithm Regulation Law, China quickly turned its attention to the next frontier of artificial intelligence: generative AI. The global explosion of AI systems capable of producing text, images, audio, and video—exemplified by tools like ChatGPT, MidJourney, and DALL·E—posed both enormous opportunities and unique risks. Beijing recognized that these technologies could reshape public discourse, influence consumer behavior, and even challenge political narratives if left unchecked. In response, the Chinese government introduced the Generative AI Regulation between 2023 and 2024, marking one of the first comprehensive attempts to govern AI content creation at scale.

The regulation applies to any service offering generative AI to the public within China, regardless of whether it is operated by domestic or foreign companies. Its overarching goal is twofold: enable innovation in a fast-growing AI sector while ensuring that AI outputs remain aligned with state-defined social, political, and ethical standards. Unlike the broader, algorithm-focused regulation, generative AI rules tackle content creation at its source, addressing the potential for misinformation, deepfakes, copyright violations, and ideological risks.

(1) Core Provisions

The Generative AI Regulation sets requirements and standards across all phases of the development and deployment of AI applications using generative AI components.

1. Mandatory Registration and Security Assessments

All generative AI providers must register their systems with the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and undergo security reviews before launching publicly. Registration requires disclosure of the AI’s technical capabilities, intended use cases, and governance processes. Security assessments ensure that systems do not leak sensitive data, produce prohibited content, or create risks to national security.

This process applies equally to foreign companies that wish to deploy AI services in China, meaning that international providers cannot sidestep compliance by operating remotely.

2. Training Data Compliance

One of the most critical elements of the regulation concerns the datasets used to train AI models. Data must be “legal and appropriate,” excluding content deemed politically sensitive or morally inappropriate. This includes topics related to national history, political dissent, or information classified as harmful to social stability.

Providers must implement rigorous data vetting procedures, documenting sources and ensuring that models do not learn from prohibited material. The regulation thus enforces a content-first approach: AI can innovate, but only within the bounds defined by the state.

3. Content Moderation and Safety Mechanisms

Generative AI outputs must comply with China’s content standards in real time. Providers are required to implement active moderation tools, filtering content that violates rules, and to respond swiftly to complaints. For example, text-generation systems must flag outputs that could mislead users or produce politically sensitive statements.

Image or video-generation platforms must prevent the creation of deepfakes that could threaten public trust or personal reputation. The responsibility lies squarely on providers: they are legally liable for any prohibited content generated by their AI, a significant contrast to many Western jurisdictions where platform liability is more limited.

4. Transparency and User Accountability

Users must be clearly informed when interacting with generative AI. Outputs must be labeled as machine-generated, and in some cases, AI-produced content may require watermarking or embedded metadata to track origin.

Additionally, platforms often must require real-name registration for users accessing generative AI services. This measure allows regulators to trace misuse and reinforces China’s broader approach to linking digital behavior with identifiable individuals.

5. Balancing Innovation and Control

While restrictive in many ways, the regulation does not halt innovation. Domestic firms such as Baidu (Ernie Bot), Alibaba (Tongyi Qianwen), and Huawei (ModelArts) have rapidly developed AI content generation services, designed to meet the regulatory framework. The state promotes these domestic innovators as strategic assets, encouraging rapid deployment while ensuring outputs remain aligned with political and social guidelines. Foreign competitors, however, face steeper hurdles: access to Chinese users requires adherence to censorship rules, registration processes, and local data storage requirements, effectively creating a two-tier innovation environment—one for China, one for the rest of the world.

(2) Integration with Existing Legal Frameworks

Generative AI regulation does not exist in isolation. It is embedded within China’s broader cybersecurity, data, and personal information laws, including:

- Cybersecurity Law (CSL): Ensures AI infrastructure does not compromise critical networks or national security.

- Data Security Law (DSL): Regulates how sensitive and cross-border data can be used in AI systems.

- Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL): Controls collection, processing, and storage of personal data used for training or AI outputs.

This interlocking framework amplifies the regulatory reach. A single generative AI system may simultaneously fall under algorithmic oversight, content moderation rules, data privacy obligations, and cybersecurity standards. Compliance requires cross-functional governance, combining legal, technical, product, and policy expertise.

(3) Enforcement and Early Impacts

Enforcement is active and swift. The CAC can suspend AI services, impose fines, or require immediate corrections. Early enforcement actions have already shaped behavior: some startups retooled their models to exclude politically sensitive datasets, while platforms increased transparency around outputs. The combination of registration, data vetting, and content monitoring ensures that generative AI growth is carefully orchestrated rather than laissez-faire, reflecting China’s broader philosophy of innovation under strict oversight.

- For domestic companies, the regulation creates both constraints and competitive advantages. Compliance can be a barrier to entry but also a differentiator, signaling reliability and alignment with government priorities.

- Foreign companies face even higher compliance hurdles, often needing local partners or modified product versions to enter the market.

- For users of AI applications, the regulation ensures that AI content remains within controlled parameters, but at the cost of freedom of expression. Users benefit from safety, reduced misinformation, and predictable content, yet experience tightly monitored and state-approved digital experiences.

(4) Strategic Takeaways

China’s generative AI regulation demonstrates a unique model of governance: fast-moving, prescriptive, and state-aligned, yet still designed to foster domestic innovation. The country is effectively setting global precedents for AI content oversight, influencing policy debates in regions seeking stronger national control over AI systems. For multinational firms, the lesson is clear: successful operation in China requires not only technical excellence but full alignment with the political, social, and legal ecosystem.

But of course, this transparency comes with its own limitations and should not be treated naively. China's long-term stric steering of content, political discourse and personal fredom of speech must be taken into consideration here to full extend and cannot be neglected.

In conclusion, the 2023–2024 generative AI rules build on the foundations of the Algorithm Regulation Law, creating a comprehensive framework that governs both how AI works and what it produces. By tightly integrating registration, training data controls, content moderation, transparency, and liability, China has become the first major economy to regulate AI content creation in real time, offering a vivid model of innovation under governance that the rest of the world cannot ignore.

6. Middle East: AI as a Growth and Innovation Strategy

The Middle East has emerged as a region where AI is less about regulation per se and more about strategic economic transformation. Unlike Europe, which emphasizes risk mitigation and fundamental rights, or China, which prioritizes state control, Middle Eastern nations are using AI as a lever for innovation, economic diversification, and global competitiveness. Countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia view AI as a catalyst for national growth, smart city development, and technological leadership, creating a regulatory environment that is light-touch, forward-looking, and highly flexible.

In the United Arab Emirates, the UAE AI Strategy 2031 provides a clear example of this approach. The government emphasizes innovation-friendly policies, supporting startups, research centers, and public-private collaborations, while ensuring that AI adoption aligns with ethical principles and societal well-being. Regulatory obligations are limited compared to the European Union or China; the focus is on enabling deployment and experimentation rather than imposing strict compliance hurdles. At the same time, authorities promote transparency, accountability, and responsible AI through non-binding guidelines, ethical codes, and advisory councils. For businesses and investors, this creates an environment where experimentation is encouraged, but companies must still navigate cultural expectations and evolving standards of responsibility.

Saudi Arabia offers a complementary yet slightly different model through its National AI Strategy, which emphasizes government-led adoption and integration across public services, healthcare, education, and energy sectors. Here, the state actively drives AI projects as part of a broader vision for economic diversification, reducing dependency on oil revenues and fostering a knowledge-based economy. While formal regulations are limited, government oversight is strong: companies operating in strategic sectors must align their AI initiatives with national objectives, participate in centralized platforms, and report on AI performance and outcomes. This approach ensures that innovation is rapid but strategically guided, minimizing risks while capturing economic benefits.

Across the Middle East, AI policy is often intertwined with the region’s smart city initiatives. Dubai, for instance, has implemented AI in traffic management, public safety, and administrative services, leveraging algorithms to optimize efficiency, reduce costs, and enhance citizen services. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh are pursuing similar projects, combining sensor networks, predictive analytics, and AI-driven urban planning. In these contexts, regulatory focus is pragmatic: the goal is to facilitate adoption, ensure public trust, and encourage collaboration between government agencies and private providers rather than to impose prescriptive, punitive rules.

The Middle East’s AI regulatory approach has several implications for companies. First, it provides high agility: firms can deploy AI solutions faster and test innovations at scale without waiting for extensive regulatory approval. Second, it demands a strong alignment with national priorities. Unlike Western markets, where compliance may be the primary concern, in the Middle East, success often depends on demonstrating how AI projects contribute to government objectives, from economic diversification to public service enhancement. Companies must therefore combine technical capabilities with strategic vision, partnering closely with government agencies, universities, and research centers.

For foreign businesses, this environment presents both opportunities and challenges. The relative lack of binding legislation reduces barriers to entry, but it also creates uncertainty. Policies and guidelines can change quickly, reflecting shifting national priorities, and enforcement mechanisms may be informal or discretionary. Understanding the political and strategic context is therefore essential: companies must anticipate policy shifts, engage with local stakeholders, and integrate cultural and ethical considerations into AI deployment.

From a societal perspective, Middle Eastern AI strategies aim to maximize economic and social impact while mitigating risk. Citizens benefit from smarter urban infrastructure, improved government services, and more efficient healthcare delivery. However, the absence of extensive binding laws also means that protections around personal data, algorithmic bias, or AI errors may be less robust than in the EU or the U.S. Individuals rely on ethical codes, company practices, and emerging government oversight rather than comprehensive legislation to ensure that AI is used responsibly.

A striking example of the region’s approach is the Dubai Police’s use of AI in predictive policing and smart traffic management. Algorithms help allocate resources efficiently, optimize traffic flows, and anticipate incidents before they occur. While highly innovative and beneficial, such applications raise questions around privacy, bias, and accountability. Unlike Europe, where citizens could appeal to strict legal protections, Dubai relies on operational oversight, internal governance, and adherence to ethical principles rather than statutory rights. Businesses developing these systems must therefore consider both technological performance and ethical implications, balancing innovation with social responsibility in a region where legal enforcement is lighter but reputational and strategic stakes are high.

In addition to urban and public service applications, the Middle East is leveraging AI to stimulate private-sector innovation. Free zones, incubators, and accelerators in the UAE and Saudi Arabia provide funding, mentorship, and infrastructure for AI startups. Companies experimenting with AI for finance, logistics, healthcare, or energy can scale rapidly, benefiting from supportive policies, government contracts, and access to data partnerships. Here, the emphasis is on rapid adoption and measurable outcomes, with governments often acting as both enablers and early customers for new technologies.

Ethics remains a core concern, even in the absence of binding rules. Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia have issued guidance frameworks emphasizing transparency, fairness, and accountability. These documents, while non-binding, function as soft law instruments: companies are expected to integrate them into governance processes, employee training, and system design. In effect, the region demonstrates that regulation does not always require legal penalties to influence behavior; a combination of incentives, oversight, and strategic alignment can shape responsible AI use.

Looking ahead, the Middle East is likely to maintain this innovation-driven, light-touch regulatory approach while gradually introducing more structured legal measures as AI becomes increasingly pervasive. Companies operating in the region should monitor policy developments, participate in ethical advisory councils, and proactively document compliance with emerging standards. Those that do will benefit not only from early market access but also from enhanced credibility with governments, investors, and end-users.

In conclusion, the Middle East represents a third model of AI governance, distinct from the structured risk-based EU framework, the U.S. patchwork system, and China’s state-controlled approach.

- Regulation is light, flexible, and innovation-friendly, yet strongly aligned with national growth strategies.

- For businesses, this creates opportunities to deploy AI rapidly and experiment with novel applications, provided they understand the strategic context and integrate ethical practices.

- For society, the focus is on maximizing the economic and social benefits of AI while relying on emerging oversight mechanisms to prevent harm.

The Middle East’s approach illustrates that AI governance can be dynamic, growth-oriented, and culturally aligned, offering lessons for other regions seeking to balance innovation with responsibility.

7. Comparative Insights and Global Implications: East, West, and Emerging Markets

Stepping back from the regulatory landscapes of the European Union, the United States, China, and the Middle East, a broader picture of global AI governance emerges. Regulation is no longer optional for international companies, nor is there a single, harmonized model. Each region pursues a distinct philosophy, balancing innovation, societal priorities, and risk mitigation in ways that reflect cultural, political, and economic contexts. For businesses, understanding these differences—and their implications for strategy, compliance, and innovation—is now critical. For users and society, these variations determine the level of protection, transparency, and trustworthiness of AI systems.

In Europe, regulation is structured, risk-based, and rights-focused.

The Artificial Intelligence Act classifies AI applications by potential harm, imposing the strictest obligations on high-risk systems in healthcare, credit scoring, law enforcement, and other areas that directly affect human lives. Compliance demands rigorous risk management, robust data governance, comprehensive documentation, and human oversight.

The EU’s approach is deliberate, prioritizing transparency, accountability, and alignment with fundamental rights. While burdensome, it provides clarity and predictability: companies know the rules in advance and can integrate compliance into design and operations. Historically, Europe has exported its regulatory philosophy globally. The GDPR reshaped privacy standards worldwide, and the AI Act is poised to set a new benchmark for “trustworthy AI.” Companies that embrace early compliance can transform it into a competitive differentiator, signaling ethical and responsible practices to customers, investors, and partners.

By contrast, the United States presents a fragmented, sectoral approach.

There is no comprehensive federal AI law; instead, governance relies on soft law, technical standards, and state-specific initiatives. The White House’s AI Bill of Rights offers guidance on fairness and transparency, while the NIST AI Risk Management Framework provides technical and governance recommendations. States like California, Illinois, and New York have introduced rules that range from enhanced privacy protections to restrictions on biometric use and employment-related AI tools. Federal agencies such as the FTC, EEOC, and CFPB actively enforce existing consumer protection, anti-discrimination, and financial laws against AI misuse.

This patchwork creates a landscape where compliance is partly voluntary, partly mandatory, and where companies must often follow the strictest state rules as a practical national standard. For businesses, the U.S. system demands flexibility, foresight, and proactive governance, while offering opportunities to demonstrate leadership in ethics and responsible AI use.

China offers a third paradigm: rapid, state-driven control.

With laws such as the Algorithm Regulation Law of 2022 and the Generative AI Regulation of 2023–2024, China tightly governs AI operations and outputs. Companies must register algorithms, validate training data, moderate content in real time, and comply with cybersecurity and personal information laws. Enforcement is swift and decisive: regulators can suspend services, levy fines, or mandate operational restructuring. While highly controlled, the system allows domestic companies to innovate within clear parameters, while foreign businesses face substantial barriers to entry. China’s model demonstrates how state oversight can coexist with technological advancement, creating a dual-speed AI market where compliance is a prerequisite for access and growth.

Emerging alongside these three is the Middle East, which presents a fourth paradigm: growth and adoption first, with emerging governance.

Countries like the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia treat AI primarily as a tool for economic transformation, innovation, and strategic diversification. The UAE AI Strategy 2031 emphasizes innovation-friendly policies, ethical advisory frameworks, and experimentation-friendly regulations. Saudi Arabia’s National AI Strategy focuses on government-led adoption in public services, education, healthcare, and energy, linking AI deployment to national economic objectives. Unlike the EU, U.S., or China, formal legal obligations are limited; the emphasis is on rapid adoption, measurable outcomes, and alignment with strategic priorities. Smart city initiatives, predictive traffic systems, and AI-driven public services illustrate how governments leverage AI to enhance efficiency, improve citizen services, and foster domestic technological leadership. Companies benefit from light-touch regulation and rapid market access, but must carefully align projects with national priorities and ethical expectations.

So, what do we learn from this comparison?

This comparative analysis highlights several insights. First, no single global model exists. Compliance in one jurisdiction does not guarantee compliance elsewhere. European transparency rules may require adjustments for China’s content moderation, while U.S. companies must monitor state-level law enforcement alongside federal guidance. The Middle East, while less prescriptive, requires alignment with national strategies and ethical frameworks. Regulatory fragmentation complicates product design, operational planning, and cross-border deployment.

Second, despite these differences, there are shared underlying concerns. Europe emphasizes human rights and systemic safety. The U.S. focuses on fairness, consumer protection, and anti-discrimination. China prioritizes national security, social stability, and centralized oversight. The Middle East stresses ethical adoption, economic benefit, and responsible governance. Across these approaches, regulators universally recognize AI’s power, potential harms, and societal impact. Responsible AI practices—bias mitigation, transparency, documentation, and human oversight—are increasingly global best practices, even if the legal context varies.

Third, the interplay between regulation and innovation is nuanced. Stringent rules, as in the EU, provide predictability and build trust, signaling ethical operations to customers and investors. China’s strict oversight enables controlled but rapid domestic innovation. The U.S. offers flexibility, with a reputational advantage for proactive adopters of multi-jurisdictional best practices. In the Middle East, regulatory lightness accelerates experimentation, but success depends on alignment with government objectives and social expectations. In every scenario, regulation shapes corporate governance, public trust, and competitive positioning, rather than simply imposing costs.

High-profile examples illustrate these dynamics.

European scrutiny of recruitment algorithms addresses bias and discrimination. U.S. state-level BIPA litigation has produced multi-billion-dollar settlements for unauthorized biometric data collection. Chinese enforcement has temporarily suspended services or forced compliance-driven restructuring for digital platforms. In the Middle East, AI deployment in smart cities highlights operational and ethical stakes, emphasizing alignment with national priorities rather than strict legal compliance.

Companies ignoring these regional nuances risk fines, litigation, reputational damage, and operational disruption. Conversely, strategic integration of regulatory requirements and ethical standards creates a competitive edge and market credibility.

From the perspective of society and individuals, global variation results in uneven protection. Europeans enjoy strong legal rights to understand and challenge AI decisions. U.S. citizens face mixed protections depending on state jurisdiction. Chinese users experience controlled outputs and enforced safety, shaped by government priorities. In the Middle East, citizens benefit from innovation and efficiency, but rely on ethical codes, government guidance, and corporate responsibility rather than binding legal guarantees. Understanding these differences is critical for evaluating AI’s societal impact.

Looking ahead, several trends will shape AI governance. International collaboration among regulators is increasing, with jurisdictions learning from one another. Technical standards such as ISO/IEC guidelines or the NIST AI Risk Management Framework will become key tools for cross-border compliance. Attention will shift from individual AI systems to ecosystem-level governance, addressing supply chains, third-party models, and cumulative societal impacts. Companies that anticipate these developments and integrate multi-jurisdictional compliance and ethical standards will turn regulatory complexity into a strategic advantage.

In conclusion, global AI regulation now presents four distinct paradigms.

- Europe embodies strict, risk-based compliance with heavy penalties.

- The U.S. relies on fragmented, sectoral enforcement and soft guidance.

- China implements state-driven, compliance-first control.

- The Middle East emphasizes growth, adoption, and innovation, supported by emerging governance and ethical guidance.

While approaches differ, all recognize AI’s transformative potential and attendant risks.

- For businesses, success requires strategic alignment, proactive compliance, and ethical design across multiple jurisdictions.

- For society, the challenge is to ensure that AI deployment is safe, responsible, and beneficial.

Navigating this complex landscape is no longer optional; it is essential for developing, deploying, and profiting from AI technologies in a globally interconnected world.

8. Practical Guidance for Businesses: Navigating Global AI Regulation Responsibly